Should Developers Care about Interpretability?

Thariq Shihipar - · 6 min read

Arguably the biggest breakthrough in LLM research this year has been in interpretability- the ability to understand what a LLM is “thinking”.

The most famous example is Anthropic’s Golden Gate Claude, though this work isn’t limited to text, researchers are also working on images, voice and even protein models.

But while interpretability is most often discussed in the context of research & AI safety, it also offers a promise to developers of more fine-grained control and reliability from their models.

How does Interpretability and Steering work?

The best foundational explanation is in the Golden Gate Claude paper which is both thorough and easy to read, but I have tried my best to summarize interpretability and steering work from the view of an AI dev.

Interpretability:

- You can breakdown a LLM into a set of ‘features’ which describe different concepts e.g. The Golden Gate Bridge, the arabic language, etc.

- Given some text input, you can figure out which one of these features activate in the LLMs “brain”. This happens quickly, cheaply and reliably, the same text will always activate the same features.

Steering:

- When generating, you can activate a particular feature at a particular intensity.

- Different features at different intensities will have different effects. For example, the Arabic feature at sufficient intensity will make your model speak Arabic. Turning up the golden gate bridge feature all the way will make your model think it’s the golden gate bridge.

- You can steer on the fly by activating and deactivating features based on the tokens and other features you see. For example, when you detect the start of a coding sequence, you might turn up certain features related to coding in the language.

The Promise

At the Anthropic hackathon, Dario Amoedei described how interpretability is maybe not the right word to describe what they are doing.

The other side of interpretability is steering, preciseness & reliability. If interpretability delivers on its promise, developers should have a level of control over their models that has not been possible thus far.

What are the applications?

1. Capturing style that cannot be described in words

One of the hardest problems with LLMs is capturing and reproducing a specific style.

In a prompt you might say: “friendly and concise”, but you might actually want something like: “70% friendly, 50% concise, 80% professional”.

Or you may want to emulate a specific person, but find that the prompt: “be more like [person]” doesn’t work.

Interpretability and steering allows you to break down a style into a set of features, and then steer the model by activating and deactivating those features.

In fact, research is already showing that you can steer text, voice and images.

Examples

Text Styles

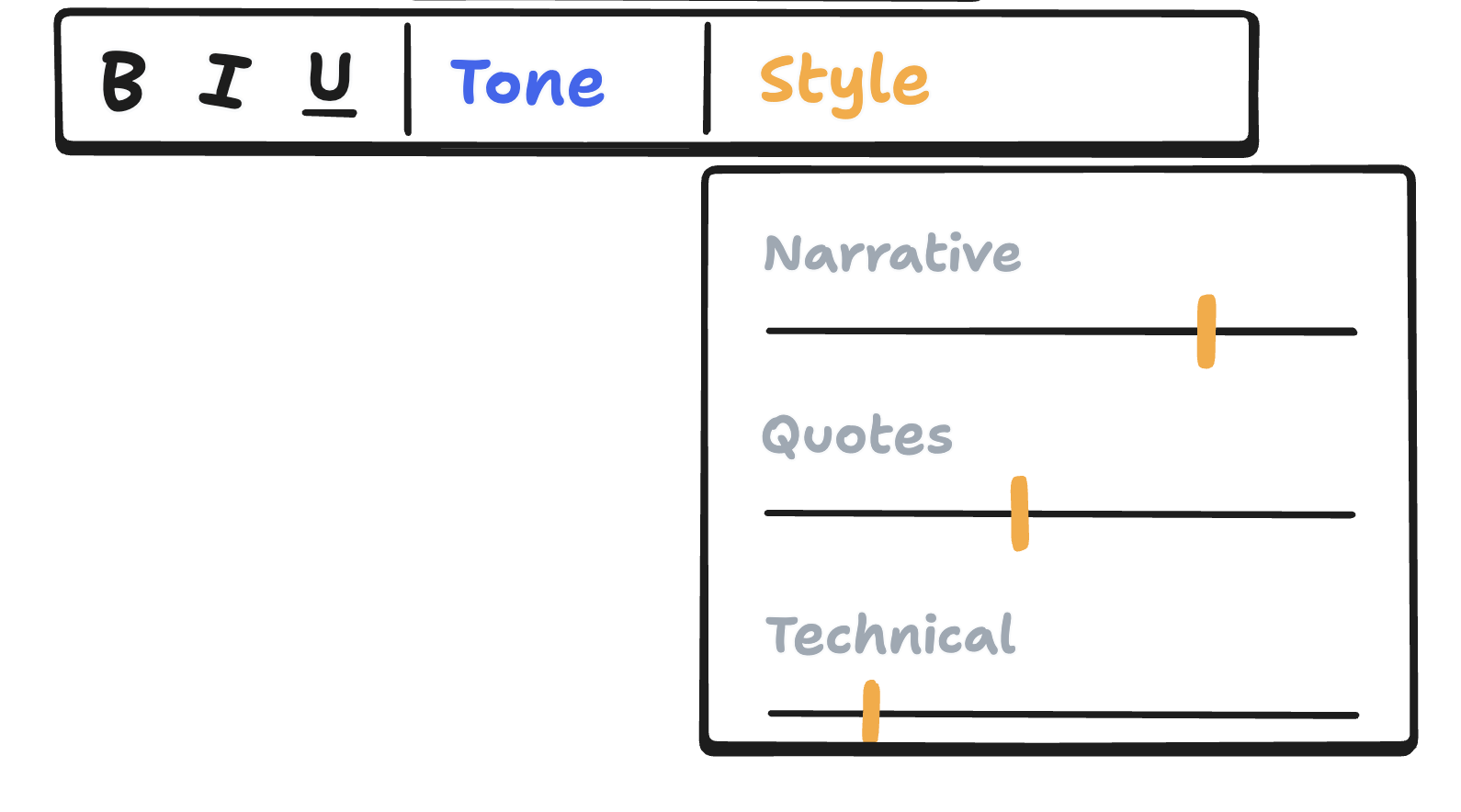

Linus writes about steering text generation by training a text embedding classifier.

Goodfire.ai provides a tool for steering llama models based on features that you detect.

Voice Styles

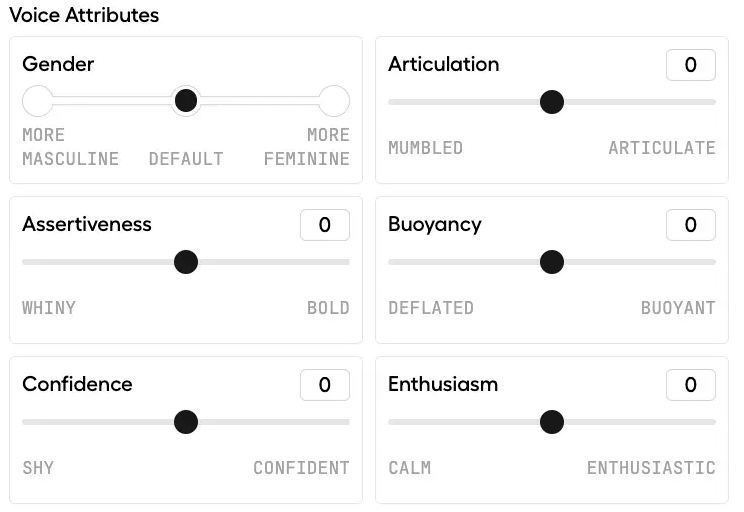

Hume is able to break down a voice into components, and then let you tune up and down features like “nasal” or “crisp”

Image Styles

Featurelab.xyz by Gytis shows how images can be broken down into distinct features, and also how you can generate images by composing those features together.

2. Less need for RLHF

RLHF (and related techniques) have so far been the primary way of creating a system personality (e.g. concise, helpful) and imposing system limits (e.g. do not respond about topics related to racism).

The problem is that RLHF famously has side effects. It can lead to “false refusals” where the AI refuses to do something that it can do (the llama paper cites 1-5% of new false refusals), and sometimes degrades quality, e.g. RLHF to be more concise, can also make a model respond with code comments that just say to fill in the code.

Steering potentially allows us to react only if we see a feature activate (eg., Anthropic has detected a ‘scam emails’ feature) and implement an intervention only then by activating another feature, or deactivating that feature.

It also allows us to choose a personality for the model by choosing particular personality and response features to activate (e.g. a sycophantic feature).

There has even been some work on ‘uncensoring’ RLHFed models through a technique called abliteration.

Most promisingly, steering happens at inference time unlike RLHF which means that API devs should be able to choose how the model is steered more specifically, vs having to rely on the model providers making large blanket choices that affect everyone via RLHF in post-training.

3. Remembering User Preferences vs User Requests

When chatting may give you a request like “tell me the capital of France” or they may state a preference like “please respond more briefly” or “speak in Arabic”

Over the course of a long conversation, these preferences may be lost in the context window. But steering allows you to recognize an important preference and save it permanently, making sure that your AI is always responding more briefly.

4. Cheap, Fast, Reproducible Classification

You may have a bunch of examples of emails that you would describe as spam, but you don’t have a way of concisely describing to the AI what “spam” means.

Right now, you could give the gpt-4o mini a set of 100 examples and ask it to classify each email. This is not bad, but it is a bit unreliable and costly.

With interpretability, you can give the AI a large set of examples of spam emails and see what features activate the most, compared to what features activate in non-spam emails.

Building this set of ‘spam features’ will allow you to essentially create a cheap spam classifier without having to train a seperate model.

What are the downsides?

1. Moving the model ‘out of distribution’

Steering is like brain surgery, prompting is like asking politely. Steering a model to overweight a feature can cause it to not just bring it up excessively (e.g. Anthropic describing at high weights how Golden Gate Claude thinks that it is the Golden Gate Bridge), but also to just generate incoherent text or text that doesn’t follow the rules of language.

2. Not understanding what a feature does

Features are labelled by a mixture of humans and machines by reading a list of output that is triggered by said features and reading what they might have in common.

However, this labeling is still early on, browsing lists of features I occasionally find myself disagreeing with how they are labeled.

Given that there might tens or hundreds of thousands of features, it seems likely that some will be mislabeled or misunderstood, which will make steering using them less reliable.

3. Activating other features & circuits

Some features activate other features in ways that are complex to understand (these are sometimes called circuits). We may be introducing other side effects while activating a feature, in the same way that RLHF introduces side effects.

There has been no wide scale use of feature steering (unless Anthropic is doing it under the hood), and so it’s hard to tell what side effects they might produce.

Conclusion

While a lot of the interpretability features are still a bit too early to show consistent reliability, they promise developers a lot more fine-grained control of models.

As a tradeoff, we should expect the next gen model APIs to get a lot more powerful but also more complicated, requiring more than just prompting and RAG to get the outputs we want.